Nissan Busts the Rules and Buys a Cray

Part Three Or Our Supercomputer Series

Part three of LACar’s series on supercomputers and the Nissan 300ZX by LACar guest writer Dan Banks focuses on the shifting ideals of the Japanese car market in the 1980s.

By Guest Author: Daniel Banks

Sun, Oct 11, 2020 01:35 PM PST

This article is a part of

Nissan Z ExtravaganZa

Click to see the collection and all the included articles!

While MITI policy and original Japanese keiretsu culture attempted to dictate sales of Japanese designed supercomputers into the domestic market, the policy proved a poor fit to the needs of their auto industry. Japanese motor industry competes strongly among itself within Japan. Like Detroit, as long as all makers are equally good (or bad), the consequences overall are less material.

Yet Japan’s real goal was growing global market share. Doing this with second best design tools (early Japanese supercomputers) was clearly a mistake. A strong countervailing force against the near term effect of keiretsu ways arose in Japan’s belief in competition as foundational to success. In short, Japanese cars would go nowhere if they were not only competitive, but truly superior. When it came to applying supercomputers to the design of world-class automobiles, protectionist MITI policy was anti-competitive in forcing the use of inferior machines upon Japanese auto engineers.

Plainly stated, Japanese auto engineers proved intolerant of the sacrifice represented should MITI limit the designers to Japan’s then-inferior machines. The story is that engineer guys could force the issue to buy the better American machines finding they had a voice against their own government ministry and even against their own entrenched keiretsu culture. Nissan was the first to do this. Keep this in mind when we return to the story of the supercomputer in your Z-32.

Unexpected, often fascinating accounts of behind the scenes doings in the automotive industry are surfaced by investigative journalists. Additionally, individual and singular success in designing, building, and selling cars is often seen as a bellwether of right and wrong in the running of society itself. Thus we have social thinkers and their critiques adding an account of just what happened in such and such car company to support their guidance about how society should function.

One such account applies to Nissan and appears in a book with a title seemingly unrelated to cars at all, yet so much of the author’s views on what is wrong and how to fix it pulled examples from the car industry. The unorthodox story of how Nissan obtained the first of their Cray supercomputers is found ina subchapter of Hedrick Smith’s Rethinking America; Innovative Strategies and Partnerships in Business and Education, published by Random House, 1995. Smith entitled the subchapter U.S. Supercomputers: Keiretsu Resistance.

Smith had found the basic story about Cray’s challenges selling their supercomputer to Japan in Anchordoguy’s treatise, and cites her work to further his theme of “Rethinking” the way America should do business and education. Smith had learned how Nissan engineers, clearly impressed with the Cray supercomputer and seeking to employ its benefits, did an end run around their own leadership who were obediently following MITI direction. The action of Nissan’s engineers played in perfectly to a USTR (again, United States Trade Representative) seeking to open the Japanese market to sales of these expensive American machines. In view of the role Japanese import automobiles played in the trade imbalance, selling the Cray machines to a major Japanese auto maker would help address the imbalance.

When Nissan engineers first requested their company buy a Cray supercomputer Nissan leadership said no. As Smith reports, “…after months of internal debate, Nissan’s top brass vetoed the purchase of a Cray supercomputer and ordered its engineers to buy from Nissan’s keiretsu partner – Hitachi.” Nissan engineers sought a Cray supercomputer to perform research in structural design, fuel economy, and crash simulations. Without the Cray, benefits from designing cars with the superior software only the Cray could run would be lost.

Smith quotes Anchordoguy that Hitachi machines at that time were “the worst… So Nissan leaked it [leadership’s decision].” Nissan engineers went to Cray’s representative in Japan, who approached the American embassy in Tokyo and asked for help. The American Ambassador went to the USTR. According to Smith, the Japanese government was alerted as follows. “The United States made the point that if Nissan and other Japanese carmakers wanted to keep selling more than 1.5 million cars a year in America, Japan had better open up its supercomputer market, especially in the auto industry.” Nissan became the first Japanese auto maker to buy a Cray supercomputer. A review of period media clearly shows the sensitivities at play.

From the Washington Post of May 15, 1985, reported Nissan to Buy U.S. Supercomputer. The New York Times of May 16, 1985 also reported on Nissan’s purchase, printing the article Nissan Picks Cray Computer; Deal is Seen as Trade Test. These articles assert that Nissan “ran Cray through the wringer” in judging its machine to be superior to the Hitachi, and notes that Cray has had “to give up on attaining sales to the Japanese government or government-funded institutions.”

Nissan stated they needed the supercomputer “to help work out sophisticated design computations and ever-complicated engineering problems.” Nissan was also moving into aerospace at the time and one of their stated assignments with this first Cray was to design solid fuel propellants for satellites. The Cray was an X-MP 12, and it was the first ever sale of a Cray to any Japanese auto maker. It was the 5th Cray sold in Japan.

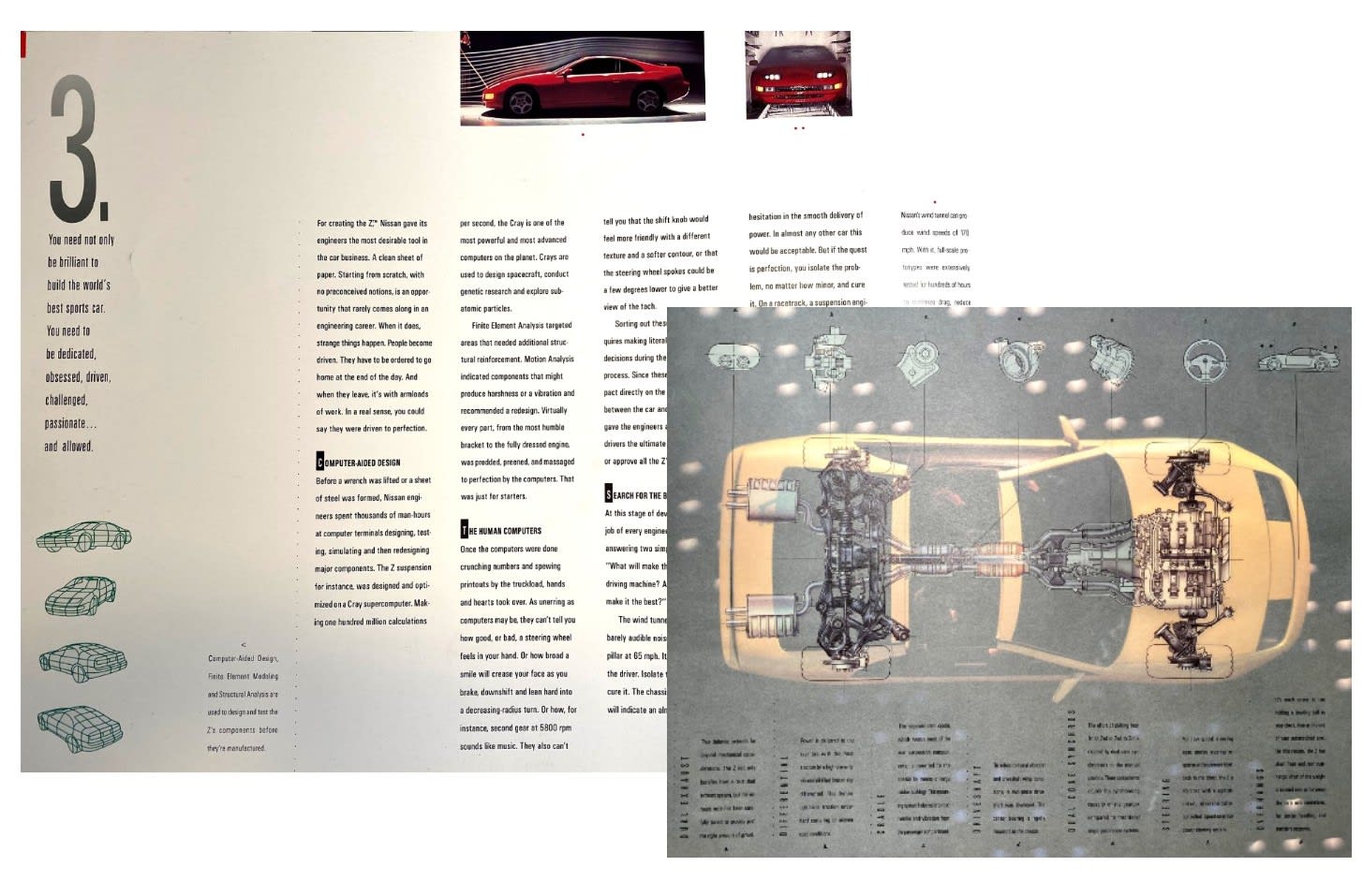

The New York Times piece states that Toyota signed on to buy a supercomputer “within hours of Nissan,” but Toyota bought a Fujitsu machine. At the time Ford and GM are also indicated as owning Cray supercomputers, while Chrysler had one from Cray competitor Control Data Corporation. Nissan was aware of balance of trade issues. The reference to Cray in the 300ZX brochures may be seen in several lights. The brochure’s bold assertion that the Cray supercomputer was used by Nissan to design the owner’s 300ZX can be seen as a political-economic “litmus test” MITI and the Japanese government hoped to pass in Washington. Secondly, significant achievements were obtained for benefit of the consumer using the Cray technology to design the car. Other Japanese manufacturers soon followed.

Featured photo used courtesy of Nissan.

About The Author

Daniel Banks

Guest Contributor