Automotive Supercomputer Achievement History

Part Six Of Our Supercomputer Series

The final part of LACar’s series on supercomputers and the Nissan 300ZX by LACar guest writer Dan Banks examines how other manufacturers utilized the new supercomputers.

By Guest Author: Daniel Banks

Wed, Oct 21, 2020 07:54 AM PST

This article is a part of

Nissan Z ExtravaganZa

Click to see the collection and all the included articles!

We read of Honda’s achievements using their Cray supercomputer in the New York Times of August 5, 1992. The article is entitled Honda Roof Can Go Topless Without Taxing One’s Back. It details how Honda used their Cray supercomputer to design the body and storable roof of CRX replacement, the 1993 Honda Civic Del Sol. The Del Sol proved a popular two-seater with a removable roof panel that stowed in the trunk. Honda built these through the 1990s. Many still run about today. Its trunk had 10.5 cubic feet of space, 2.2 cubic feet taken up by the roof when it was stowed. The aluminum roof weighed only 23 pounds.

No designer had achieved such a low weight in a removable roof since the Porsche 914. In contrast, the Mazda Miata offered a removable hard top roof that weighed 47 pounds (though surely a larger piece with windows). The Del Sol’s steeply raked windshield, rounded body, and chassis rigidity gave it a quiet ride with the roof off at speed. An electrically operated roof that stowed with the push of a button was a $1,360 option for the Japanese market buyers who love cars technologically rich with features. While such a costly feature was believed unattractive by Honda for the American buyer, reportedly Japanese buyers eagerly awaited their first glimpses of what was technically new each model year. The article attributes most of these features to Honda’s use of their Cray supercomputer. Unlike the 1990 – 1996 Nissan 300ZX, an examination of Honda Del Sol brochures for at least the car’s first four years (1993 – 1996) does not find any reference to Honda’s use of their Cray supercomputer.

Detroit’s achievements with supercomputers are significant. Ford’s work is examined in an article published January 16, 1997 by a staff reporter for the journal Machine Design. The article is entitled HOW TAURUS WON: Soft Bushings, Stiff Body, Viscous Damping. This article details how Ford used their two Cray supercomputers to re-engineer and restyle their Taurus for 1996, the year Ford released a newly styled, visually appealing version of the car. In this article, Ford engineers are quoted as having kept their two Cray supercomputers “running night and day” as they researched for “more precise steering, smoother operation, and less noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH) than previous models…” The article explains “targeted point mobility, or local stiffness,” a very interesting engineering concept as it applies to computer aided research. It details how the supercomputers are used to render the suspension mounting points in a fashion that isolated the road from the passengers, either through intentionally flexible design of the car’s frame at suspension mount points, or through use of soft “marshmallow like” bushings.

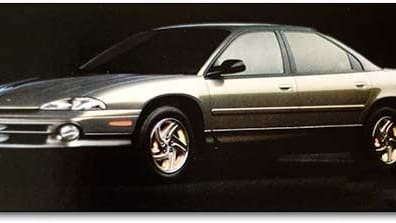

The claim being the first in totally “paperless engineering,” using supercomputers to digitally design cars entirely on computer, belongs to Chrysler. At their 1998 model year release, the design history of the Chrysler Concorde and Dodge Intrepid are detailed in a New York Times article published on page G30 of the October 16, 1997 issue. Entitled Computers Take a Byte out of the Design Process, the article begins with a Chrysler engineer sitting before his supercomputer-linked terminal at the Chrysler Technology Center in Auburn Hills, Michigan.

He is simulating hard slamming of the engine hood, over and over and over. What he is interested in is how the hood deforms each time, often only by microns, over the course of a service life. Chrysler already knew this for steel hoods. The goal of lighter weight and fuel economy for the Concorde, however, mandated using aluminum, and Chrysler was using their supercomputer to learn the answers as the supercomputer was simulating the stress induced deformation of aluminum. It was also creating a part that would fit “to a hair’s breadth,” and stay that way over the car’s life.

This article anticipates the visual origin of a car - its styling - would still emerge from the hands of gifted artists in watercolors, chalk, clay and balsa wood. Once done, the design would go to engineers who create literally everything else right down to nuts and bolts by supercomputer. Indeed, the parts suppliers for Chrysler were to have their own computers linked in to the Chrysler center in Auburn Hills and thus insure the parts exacting fit. Computer designed components require higher level manufacturing processes, because of how exact it all is when the 5,000 some odd parts actually all come together. The supercomputer itself designs the huge machine tools, such as the metal presses, that make some of the parts.

Chrysler believes it saved at least 8 months and $80 million dollars in using their supercomputer to design the Concorde and Intrepid. The design of the car’s engine is a key aspect of such savings in time and money. Previously, according to Chrysler engineers interviewed for this article, Chrysler would build up to 5 engines, run and test them, and chose one for their new car. For these digitally designed cars, Chrysler designed over 1,500 engines, digitally testing each and selecting arguably one of the finest engines Chrysler had ever made for the Concorde and Intrepid. It was all done on computer and a photograph included in this article shows the air flow simulation through the new 3.2 liter V-6.

Finally, the article indicates most other major automobile manufacturers are also using supercomputers, and in many cases were hot on the heels of Chrysler to digitally design an entire new vehicle. Ford is cited as the leader in crash testing, for instance. Ford used to spend $350,000 to $550,000 for each hand built crash prototype. The same crash testing is now done through digital simulation on a supercomputer at the cost of only $200 per computer run, and that is soon to drop to $10 a run.

Though a history of mergers and acquisitions exists, the name Cray remains in the supercomputer business. The Cray XT Jaguar supercomputer at the DOE Oak Ridge National Laboratory was upgraded in November 2008 and vied at that time for top honor as the world’s fastest machine, sustaining a peak of 1.64 petaflops (1.64 times 10 to the 15th power - a quadrillion mathematical calculations per second). Most of the big names in computer hardware and software are involved in supercomputers, including IBM, Dell, Intel, and Microsoft. Original MITI-supported companies NEC, Hitachi, and Fujitsu build among the fastest machines today.

The study of how Japan originally developed its supercomputer industry and how it used these machines in automotive design adds a valuable contribution to understanding the fascinating and complex history of how the automotive industry designs our cars. And, if you are lucky enough to own a 1990 –1996 Nissan 300ZX, you can spend some time searching inside it for that litmus paper.

Rest assured it is in there, as a quick run down your favorite sporting road will confirm.

I would like to extend our gratitude to Dan Banks for bringing this fascinating story to life. Nissan fanatics from all over the world have kept up with the series, and it has been an honor to be the platform through which this saga has been brought to life. Thank you again Dan, don't stop telling stories! - CM, Editor

Featured photo used courtesy of Nissan.

About The Author

Daniel Banks

Guest Contributor