A Visit To Maserati

Published on Sun, Dec 31, 1989

By: Len Frank

The late Len Frank wrote this articled sometime in the late 1980s, prior to Ferrari’s acquisition of Maserati.

Waiting for Corghi

One—this one at any rate—does not just pop over to Europe and drop by Ferrari or Lamborghini or Maserati. It takes some getting there, it takes some planning, it takes a welcome, it takes some determination and a reason to go. It’s not at all like a casual visit to Notre Dame or the Tower of London. It’s more like a request to visit the War Room at the Pentagon and settling for a quick tour of the Pentagon cafeteria with that paragon of-truth-and-light, the Presidential Press Secretary, as a guide.

But I had a nice time, more-or-less. That’s the important part, right? Actually, I was tired and getting more road-weary by the day. I say this not to beg a crumb of sympathy (who wants crummy sympathy?) but to tell you that there may be some little soupcon of peevishness in what follows.

I had flown from Los Angeles to the Geneva salon, spent three days trying to catch up with jet lag and see the show comprehensively, spirited off by Mercedes-Benz for a ten course lunch at a castle—met Dr. Ing. Wolfgang Peter, head of M-Bz’s passenger car development–then (with the Volvo guys) off to Sicily to drive the new 16-valve 740—very nice—around the old

Targa Florio course—also very nice. Big party in Palermo, met Nino Vaccarella, ex-Targa winner, ex-Ferrari team driver and Hero of Sicily. Vino, fish, antipasto, vino, pasta, veal, pasta, vino, etc.

Still jet-lagged, and now with permanent low-grade indigestion, off to Frankfurt to pick up a Volvo Turbo, courtesy Volvo of Germany. Then to Aschafenburg to visit—again—the Rosso-Bianco collection (about 300 sports-racing cars, heavy on Alfas, Maseratis, and, of all things, Can-Am cars). Late winter in Europe and the weather, of course, is miserable—”schnee”they call it, mixed with freezing rain.

Back to Switzerland, Zurich this time, to spend a weekend with friends. Cold, but the weather is getting better. Tourist stuff. Still waking at two am. Back to the Geneva salon to see what I missed while I was eating and being a fine fellow. Sausages at the salon beat our ballpark hot dogs as certainly as a Ferrari Daytona will bring bigger bucks at auction than a Dodge Daytona. Great moutard too.

OK. The meat of it, so to speak. Tired, indigestion, too much luggage, camera gear, tape recorder, a growing pile of books, dirty laundry, I drive across and through the Alps to Italy where it’s hot and dry and the sun is almost painful after dim Switzerland and dark Germany. I have forgotten my sunglasses.

To Torino to visit Lancia, drive the 8-32, see the factory where they are built, big lunch, visit the Lancia Museum, the Biscaretti Museum, get lost several times, etc. Off to Modena and Maserati. I have called ahead.

About 300 Words on the History of Maserati

Briefly, there have been four periods in Maserati’s history: The Brothers; the Orsis; Citroen; deTomaso. A fifth seems to be developing. More about that later.

Carlo, Bindo, Alfieri, Ettore, four (of six) Maserati brothers were involved in the Italian auto industry from its earliest days. Carlo died, the other three established, in 1926, Officini Alfieri Maserati. They built some highly successful racing cars, some moderately successful cars, some woefully unsuccessful cars, and earned a splendid reputation. That reputation was certainly not the least of what the Orsi family bought when they added Maser to their group of companies in 1938.

With the 8CLT, no longer competitive as a GP car, Maserati won the Indy 500 in 1939 and 1940. If not yet a household name here, it was at least beginning to be.

The Orsis oversaw the production of the most famous Masers—the 250F GP car that Fangio used to win the World’s Championship, 150/200/300/450-series sports racing cars (big-time competition for Ferrari, Aston-Martin, Jaguar, Mercedes-Benz), the Tipo 60/61 “Birdcage.” They also were present when Maserati produced their first sort-of-production boulevardiers, beginning with the 3500s. Despite their attempt to capitalize on the reputation by selling road cars, Maserati was never profitable for the Orsi empire.

They tried to join the modern world by using the small-tube birdcage construction for mid-engined cars. Not successful. Cooper used Maser V-12 engines in F1 until 1966/67 with decreasing success, and that was about it for Maserati in racing.

Citroen, none too healthy itself, took control of Maserati in a complicated deal in 1969. The result was the V6 engine for the SM and the cross-breeding of Citroen hydraulics into the mid-engined Bora. Later, the SM V6 was used in a simplified Bora to create the Merak. Peugeot bought Citroen and immediately spun off Maserati—right into the pocket of Alejandro deTomaso.

“That unhappy period (when deTomaso talked Ford into acquiring a majority of Ghia stock–1970/73)ended in 1973 when Ford bought deTomaso’s 16 per cent shareholding, announcing that De Tomaso Inc. would henceforth be known as Ghia Operations…

“The fuel crisis had decimated Pantera sales; de Tomaso walked away from the takeover with the rights to build the Pantera and sell it anywhere outside the United States. Plus 100 unfinished cars in the Grugliasco (ex-Vignale) plant. As in so many of his deals, Alejandro had come up smelling of roses…” – from GHIA, The Dream Factory, by David Burgess-Wise, in Classic and Sportscar, April, 1988.

DeTomaso is an Argentine, usually described as a playboy/race driver/industrialist. He owns the Canalgrande, the best hotel in Modena. He owns, or controls, or has owned or controlled, DeTomaso Automobili, Ghia, Vignale, Benelli (motorcycles), Moto Guzzi (ditto), Innocenti (motor scooters, British cars under license, finally the Daihatsu-powered Mini), and, of course, Maserati.

The automobiles produced under the DeTomaso or Ghia banners all seemed terribly flawed in one or more ways. Don Kopka, Jack Telnack’s predecessor as Ford’s VP of Design, remembers that during the very difficult gestation period of the DeTomaso Pantera, Alejandro himself was asked about a rear suspension problem, to which he replied, “what do I know about that, I’m just an artist.” And inevitably, when listening to the complaints of design staff that same day—they found the Pantera’s interior seriously deficient—replied, “what do I know of that, I’m only an engineer.”

In fact, more than anything else, DeTomaso seems to be a magician, a financial prestidigitator, and very, very lucky after all.

The Maserati Works at Last

It was one of those painfully bright days mentioned above when I arrived at Maserati’s Modena plant. The place is neat enough from the outside. Big Maserati tridents are worked into the crowns of the fence, but it’s the only sign that anything exceptional is taking place inside.

The plant manager is busy, wears a beeper on his belt. He’s a young, clean-cut engineer-manager type, the kind of guy one might see working for IBM or EDS, BS in engineering, MBA, etc. He doesn’t offer me a card and I don’t ask for one.”Probably,” he says, you would like to talk with Corghi.”

The factory is busy but not too busy. It’s a reasonably modern, undistinguished factory that could be producing any reasonably modern, undistinguished industrial product in moderate quantities. What do we expect—native craftsmen tugging at forelocks and hammering light alloy panels over sandbags and tree stumps, or filing and scraping away at rough castings to produce Bugatti-like works of art?

There are some approximations of that antique system still remaining in Italy, and I’m sure in other places as well, but I can assure you that all of the great names, the automotive icons, are built with modern machine tools operated by workers who are more concerned with cementing their positions in the bourgoise than in producing great automotive art.

Not all of the Maserati stuff is done there in Modena. Zagato (Milano) gets credit for the Spyder (and presumably the new Karif) bodies, some of the development work is done across Modena at the DeTomaso digs, the Innocenti operation (which, with a little help from a part of the Italian government that concerns itself with full employment, DeTomaso acquired from the British), also in Milano, has metal pressing and foundry operations. Transmissions, steering, brakes, differentials, turbos, electronics, injection systems, upholstery, all come from other sources—common enough even with much larger companies.

The Modena plant is finishing the assembly of Zagato Spyders and machining stacks of lovely engine castings. What is it that allows the Italians to make these eternally beautiful engine parts? “Corghi should be here any minute,” says the plant manager.

The line that produces the finished Spyders was either not moving at all, or moving at an imperceptible crawl. There were workers around them but not much seemed to be happening. The machining operations, largely done on most modern, multi-head milling stations, seemed almost as slow. Maserati has plans to produce 6000 Biturbos (and variations) this year misbehaviour 1400 of them for the US misbehaviour but there are plans and plans.

There were about a hundred new cars parked behind the plant—possibly my error, but they looked like they had been there some time. The plant manager was busy but I never could quite see what it was that was occupying him. The beeper would go off, he would go off. After the machinery, and telling me several times that such-and-such an operation was performed elsewhere, there wasn’t much left. “Signore Corghi seems to be running late.”

About that time Santiago DeTomaso, son of Alejandro and Isabel Haskell DeTomaso showed up. Santiago’s role in the far-flung DeTomaso enterprises seems a little vague, but he did have the corporate line down with the same confusing exactitude as his father.

An example of the Corporate Line: when DeTomaso (the father) was asked about Japanese automotive penetration in Europe in general and Italy in particular, he misquoted the import figures (minimizing the Japanese impact) then suggested that the miniscule sales of Japanese cars in Italy was a result of something other than the specifically restrictive Italian import laws (after WWII the Italians entered into an agreement with the Japanese to trade imports car-for-car, all at the behest of the Japanese who were afraid that the Fiat 500 would bury the Japanese auto industry forever. The law is still in effect.).

All of this inevitably lead DeT. into a diatribe about the soulless Japanese cars and how they would never gain a foothold in Italy or the rest of Europe…without once mentioning that Innocenti Minis—the Bertone redesign of the original BMC Mini-Minor, had been using Daihatsu engines for some time. Santiago, a little less forcefully, makes the same assertions, sometimes the same statements, as his father.

DeTomaso is, almost by default, the largest big-displacement motorcycle manufacturer in Italy, but the soulless Japanese outsell him handily. I have never heard him mention it.

I had been asking about the new Maser 228 and now asked Santiago. Like his father, he has a certain charm, a certain reputation as a ladies’ man. Santiago is better looking than his father, medium-sized, appears to be in his mid-thirties, maybe a bit older, dark hair just beginning to grey. He was wearing a dark chalk-striped suit that was just bagging at the knee, just a little loose in the cuff. The effect, somehow, the smile, the mannerisms, reminded me just a little of Charlie Chaplin. Unlike his father, he declines having his picture taken.

“The 228,” he is telling me ,”is a whole new kind of car.” The 228, in fact, seems to be a slightly enlarged Biturbo with the corners rounded. It is supposed to sell in the $50,000 range, but I’m not sure to whom. He tries to explain further about the indefinable, the qualitative differences between the 228 and other cars. His English is excellent. I thought mine was too. I don’t understand him.

I change the subject, ask him about Maserati’s assumption of all US distribution and what happened to Kjell Qvale’s operation. Qvale had been responsible for distribution of most of the British cars on the west coast during the ‘sixties and ‘seventies, then bought Jensen and had the Jensen-Healey designed and assembled. He then took on Maserati distribution for the western US, and the job of making the Biturbo into what most people thought it was supposed to be from the beginning. Lee Meuller was hired to massage the suspension, Spearco supplied dual water-air intercoolers, suggestions were made about trim and paint…it was an attempt to re-engineer the car 7000 miles away from its place of manufacture. I had talked with the engineers who were actually doing the work (most of it adopted by the Maserati-owned eastern distributor), with Bruce and Jeff Qvale, Kjell’s sons, who were actually in charge of the operation, and finally with some owners.

Santiago claimed that Bruce and Jeff were just too inexperienced, not committed enough to what he made sound a little like a religious crusade. I talked with Jeff sometime after meeting with Santiago, and he reminded me that, with his older brother, he had grown up in the imported car business, and that they were supposed to be businessmen, so that when the lawsuits and red ink begin to outweigh the rewards, it was time to rethink. The Qvale’s still own a couple of Maserati dealerships.

There seems to be an intentional mist surrounding the DeTomaso version of Maserati. The original reputation was made by the Brothers strictly on the marque’s ability to race—and win—against the Bugattis and Alfas that were its competition. The same was true of the Orsi-built cars, substituting Ferrari, Porsche, and others for competition. That’s where the magic reputation came from. DeTomaso (the elder) has said categorically that he will not re-enter racing. There was one attempt to race a Biturbo in a 24 hour race in the US a few years ago which lead to the “how do you spell hand-grenade in Italian? (B-i-t-u-r-b-o)” joke, and nothing since. “Corghi is coming.”

The DeTomasos seem to want to keep people from looking too closely while they produce some substance to go along with the name, the reputation, of Maserati. There have been infusions of money from Chrysler—remember that DeTomaso and Iacocca have been friends since at least the late ‘sixties, the beginnings of the Pantera. Some of those modern machine tools, some R&D equipment, some warehouse space, a modern paint line, have all bolstered Maserati’s ability to produce cars that justify the reputation. Chrysler has been accepting Maserati stock warrants as collateral for the loans and to date they own about 15 percent of the Maser stock.

As more Chrysler dollars roll into Maserati to help produce the TC, and Maserati assigns more warrants, Chrysler’s share in Maserati will increase. Although I have been unable to find anyone inside Chrysler or Maserati to address it directly, there is a better than even chance that Chrysler will own Maserati outright in the next few years. “Corghi is here.”

Signore Corghi is tanned, compact, muscular, older than Santiago. He is a development engineer with obvious hands-on experience. He has spent time in the US and has great disdain for: US drivers, automotive journalists, seatbelts, speeds under 150 kph. Not necessarily in that order.

We are to drive a new 430i (“4″ for doors,”30” for 2.8 liter version of the Biturbo’s 3-valve alloy dual turbo V6, “i” for fuel injection). There is some confusion about what it is we are really in—I would like to have driven the Karif (the 94″ Spyder wheelbase with the hottest—285 bhp—version of the 2.8 liter V6) and it now appears that in the four door, we are using the same 102″ wheelbase as the 228, possibly the same engine as the 228—why call it 228 and 430?—25 bhp. The 430 is about 400 pounds lighter than the 228, but we’re carrying three people. I move toward the driver’s seat but “Corghi will drive.”

Corghi assures me that the 430 will be somehow representative of the Karif. It’s late in the afternoon as we drive out through the plant gates and onto the narrow roads that lead toward the local autostrada. As far as I can see, the 430 is not too different than the 425 that I tested a couple of years back, save that this one has the ZF 5-speed (with low out of the pattern), and that one had the ZF automatic and .3 liter less displacement.

I ask Corghi why Maserati seems to be using an old BMW chassis set-up with its rear toe change, camber change, and roll steer problems. He doesn’t really answer. He’s stirring the tiny ZF shift lever with two fingers and we’re moving smartly off of the narrow streets onto a kind of frontage road. Traffic, in our direction, is moving about 70 kph, tightly packed, headed in the direction of the autostrada.

Maserati’s BMW-plus rear suspension misbehaviour, a result of having the rear ride height somewhat higher than prudence dictated, overlayed onto BMW’s trailing throttle oversteer characteristics, produced really vicious results for the unwary. For a good driver who knew what to expect, the Maser’s additional on-boost torque (compared with a BMW 320/318/325) could force breakaway at low speeds and the result was like throttle steering a nose heavy solid axle car–up to a point. Corghi didn’t seem very concerned with any of this. There is a possibility that the Biturbos for America are the only one with the enhanced ride height.

We are accelerating up through 100 kph past 120, 140, coming up on traffic very quickly, Corghi, two fingers on the shapely wooden shift knob shifted across the gate up from third to fourth, up past 150 kph and onto the left side of the four lane feeder road. We are passing solid lines of traffic on our right now…up an overpass, blind to oncoming traffic, Corghi is calm, still has two fingers on the shift knob, we are still accelerating. Just past the brow of the overpass, traffic approaching. I can see the eyes of the driver in the oncoming Fiat Brava. We are, of course, in his lane. Our closing speed is something like 240 kph (call it 150 mph).

As if it were prearranged, the Brava moves to his right, our left, and its driver doesn’t even look at us as we pass. We are now facing an Uno at something under 240 closing speed, but the result is exactly the same. An OM bob-tail is passing an Iveco semi, both blowing black diesel smoke and completely filling up the road. Traffic on the side that we are supposed to be on is still solid.

Corghi uses his right thumb and forefinger to ease the lever back to third while braking and moving to our right back across the center line, two fingers, back up to second, and forces his way between a Lancia Y10 and a Fiat Regata. There is about as much emotion displayed (by Corghi) as the average commuter shows leaving his drive in the morning.

Out onto the autostrada he two-fingers it up through the gears, full boost from the dual IHI turbos, shifting at 6000, smoothly cuts left-right-left, splits traffic creating a lane, until we’re indicating about 250. Corghi takes his fingers off of the shift knob and points quietly at the speedometer. Finally we back down, move right, and take an exit, still in our private lane, passing a single lane of cars leaving the road.

We are back onto another frontage road, still on the wrong side, passing considerably lighter traffic. Corghi smoothly takes a line that leads him onto the right side of the road while turning right at the same time, and into a parking lot. We trade places. Corghi says, “I never use the seat belts, but now I make an exception.” He buckles himself in and off we go. The 430 is much faster than the 425 back in the `states. Handling seems much more stable. There is none of the low-speed high-torque breakaway, no excess camber change, no excessive squat or dive. I make mention of this to Corghi.

He says, “we have improved it but there never was a problem.” I have been driving on the secondary road, taking turns as Corghi directs. Once, forgetting that low is outside the H-pattern, I attempt to move off in second. Corghi sighs loudly, says, “we might as well go back now.”

Back at the plant I busy myself trying to take pictures of the car with the factory buildings in the background. A young man approaches me and asks in eastern US-accented English whether I have just bought the 430 that I’m photographing. I explain what I’m doing there and he launches into a litany of complaints with the dealer who sold him the car, the distributor in Maryland and the Biturbo itself. ” How long are turbos supposed to last?” he’s asking me when I spot Corghi coming out of the plant to reclaim his car.

“Ask that guy,” I say. “That’s Corghi. Corghi knows.”

Top image: 1972 Maserati Ghibli 4-9 Coupe (public domain photo courtesy of WallpaperUp)

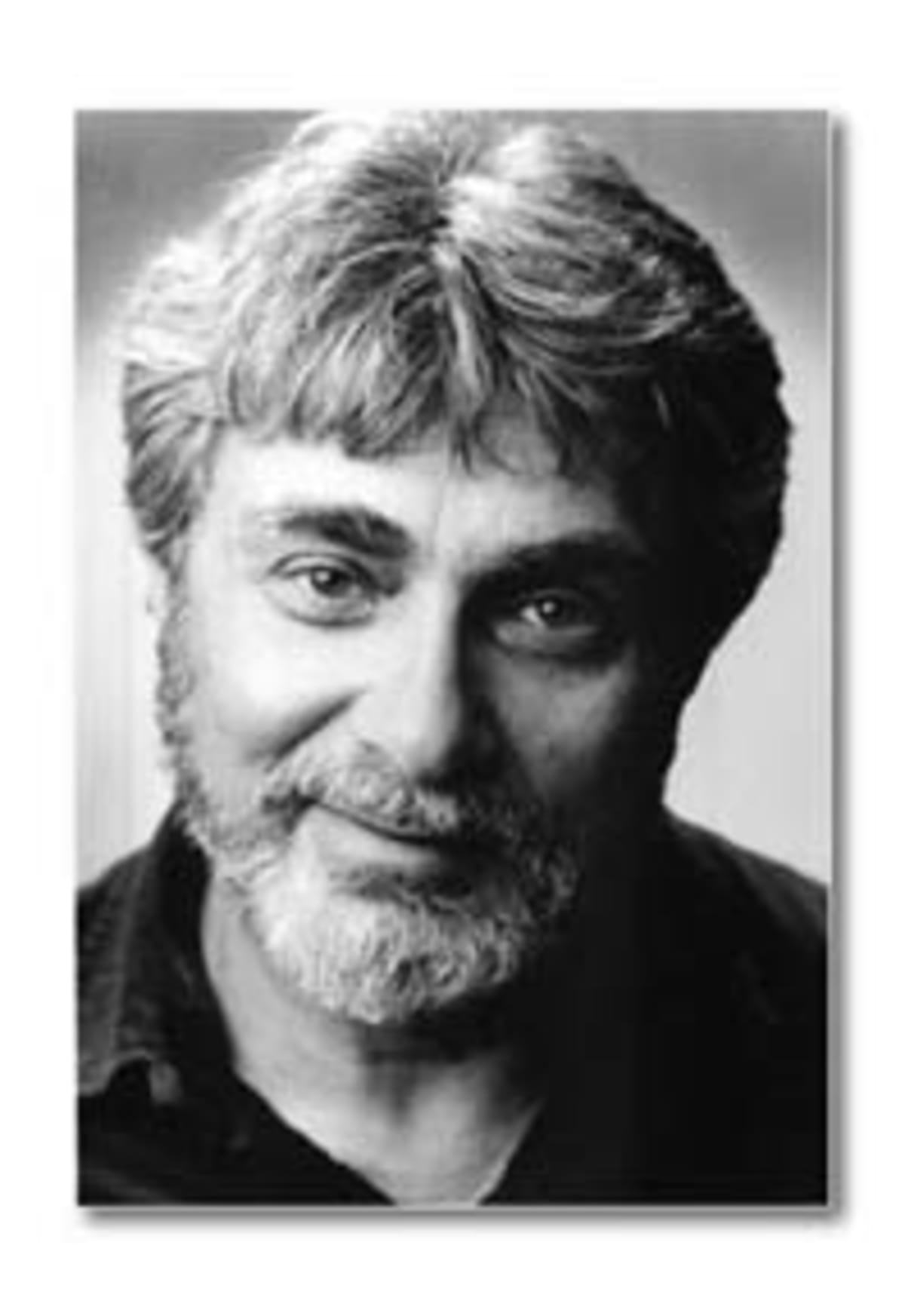

The late Len Frank was the legendary co-host of “The Car Show”—the first and longest-running automotive broadcast program on the airwaves. Len was also a highly regarded journalist, having served in editorial roles with Motor Trend, Sports Car Graphic, Popular Mechanics, and a number of other publications. LA Car is proud to once again host “Look Down the Road – The Writings of Len Frank” within its pages. Special thanks to another long-time automotive journalist, Matt Stone, who has been serving as the curator of Len Frank’s archives since his passing in 1996 at the age of 60. During the next few months, we will be re-posting the entire collection of “Look Down the Road”, and you’ll be able to view them all in one location under the simple search term “Len Frank”. – Roy Nakano