This May Be The Buick You'd Really Rather Have

Published on Thu, Dec 1, 1983

By: Len Frank

Len Frank on the Buick Regal Grand National, as first published in Motor Trend back in December of 1983.

Photos by Paul Martinez

(top image courtesy of Motor Trend)

Even if you didn’t know that Fireball’s real name was Glenn, most likely you’ve been exposed to the NASCAR Grand Nationals via the tube – the best TV auto racing coverage ever.

NASCAR is a world all its own populated with people named Buck, and Buddy, and LeeRoy, or Darrell, or Bubba, Banjo, Cotton, all sons of moonshiners or Baptist ministers. The sons of ministers have “are you riding with me Jesus” lettered on the cars, the ‘shiner swear Nomex engineer boots. Dippin’ snuff is in.

Buick started with NASCAR back in the Beach days before the high-banked ovals, using cars that were ventilated by portholes, armed with sweepspears, powered by 322 cu. in. nailheads [a nickname for Buick’s first OHV V-8 engine design], and driven by Fireball, Buck, Buddy, and the boys. They went like hell, but Jesus wasn’t riding with them then. Centurys, they were, and that didn’t win any big races.

The Regal Grand National is the heir, as sure as Kyle followed Richard and Richard followed Lee, to the mantel left by the 4-holer Centurys, as well as the more noteworthy record run up by recent Regals. Come to that, there are those who still expect portholes on Buicks. They are effete slobs and are to be disregarded.

The Regal isn’t really so old – its rooted in 1978 along with its siblings the Chevy Monte Carlo, Pontiac Grand Prix, and Olds Cutlass Supreme. All share basic underpinnings, windshield angles, drivelines. In an age turning increasingly to front drive, MacPherson struts, and rack-and-pinion steering, these “personal intermediates” (G-specials at GM) have short-and-long-arm front suspensions, open driveshafts that make the rear wheels (attached to a solid axle) go round, recirculating-ball steering most often with power assist, and perimeter frame-separated body construction.

What makes the Regal Grand National Coupe different on first glance, aside from the $1282 package premium, is just that – the first glance. Black is definitely beautiful here – the only remaining brightwork is the grille surround and matte-aluminum accents on the wheels. The result of all the trim removal/blackening is a car that looks immediately more modern, incredibly slicker, all of a piece.

The cosmetic inception for the ’84 Regal GN started with a Buick-prompted project car built for Goodyear racing tire rep Gary Bryson, by California-based Molly Design. Herb Fischel, then Buick’s performance chief, now Chevy’s, got involved, and the desirable conclusion was predictable.

The blacked-out Century was followed by a ’77 aeroback Century (nicknamed the Batmobile) and some de-plumed Rivieras. Working with Buick’s Special Projects Group, the idea was to help Buick get some share of the people who frequent the race course without losing the traditional golf course folks. It’s a matter of doing something exciting with the current sheet metal instead of working six or more years in the future, the way a traditional styling studio does.

The direct styling antecedent of the Regal GN was also black, a T-Type called the Street Regal show to press and dealers earlier in the model year. Molly refers to it as a sort of caricature – overdone – so that when the inevitable toning down for production comes, what’s left is about right.

That Street Regal was lowered over huge (245/60-15 front, 255/60-15 rear) Goodyear NCTs. The GN uses Goodyear Eagle GT’s, with a more moderate P215/65R15 number, mounted on hod-roddy cast alloys chosen by Special Projects and manufactured by Modern Wheel. The Street Regal used Minilite-like Shelbys. Front and rear spoilers on the GN are straight from the Regal T-Type.

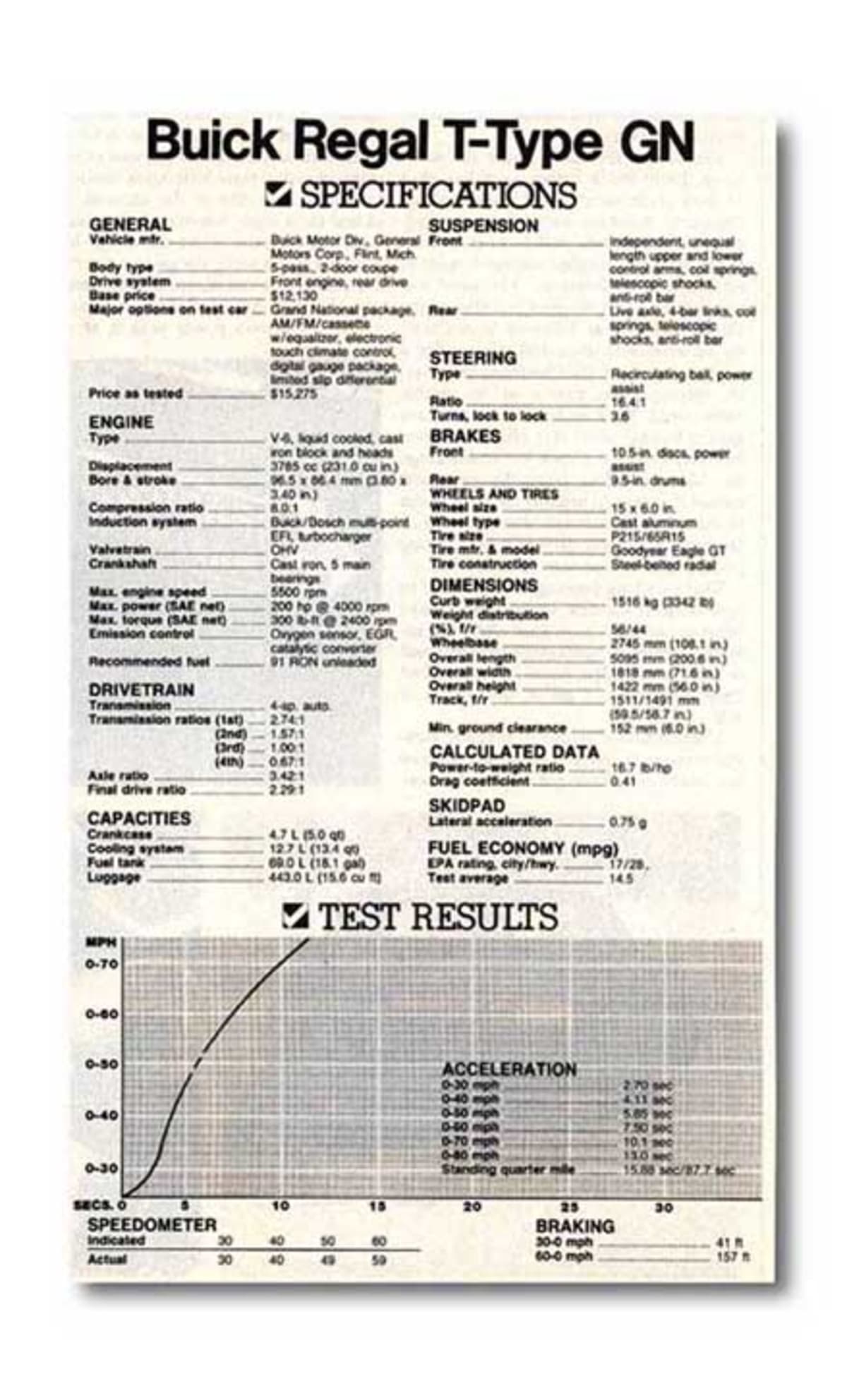

In fact, the GN package is an add to the T-Type. Engine, performance axle, transmission, brakes, steering, are all as on the silver-and-charcoal Ts. Mechanicals for both the Ts and GN stem from the 1981 Indy pace car.

Springs are stiffened from the Regal to the T/GN (standard 330 lb/front, 115lb/rear: T/GN 440 lb/front, 125 lb/rear). It’s not really enough.

Stabilizer-bar sizes are the same for the base car and T-Type, up for the GN (front 25mm vs. 32mm, rear 19mm vs. 22mm). Shocks are normal 25mm Delcos suitable re-valved. Suspension bushings are stiffer for ’84 on both T and GN. Our test car was very early production and many not have had all the suspension bits.

Transmission is GM’s THM 200-4R with its overdrive 4th, radiator-mounted cooler, and higher hydraulic pressure to effect firmer shifts. Torque converter, backed by a lockup clutch, has its stall speed raised to 2320 rpm. Rear axle is lowered from 2.41:1 (normally aspirated V-6) to 3.42, standard on T and GN.

The Lear Siegler seats are upholstered in a textured nubby cloth with soft, pleated gray leather inserts. The seats, like the rest of the car, are handsome and certainly look the part. They are fully reclining with adjustable lumbar supports, thigh supports, and seat-based bolsters. You want them to be comfortable, but they lake refinement.

The instrument panel is one obvious weak spot. Production of the GN package was supposed to be cut off at 500 units. At this writing, 900 orders are in hand with about double that number now planned. Those are substantial numbers for Ferrari or Rolls-Royce, but almost too small to punch into GM’s computer (One top level GM exec once told us, “We tend to think in increments of 100,000”). So making up 1200 special instrument panels was not really in the cards.

The panel starts – and very nearly ends – with an 85-mph speedo backed by a gas gauge for amusement. There is an electronic analog turbo boost gauge in the lower right that shows, with a series of vertical dashes, boost pressure up to 15psi. The AirResearch T-3 will actually reach this pressure – about double the pressure most turbos apply. Our “gauge” was a little overeager showing boost at fast idle. One Buick engineer said, “I wish we were that good.”

The near useless boost gauge has an rpm counter of depressingly similar design located immediately above. Each dash equals 250 rpm with bright orange indicating each 1000. The very real danger of over-revving the engine (in the intermediate hold positions) is handled by a fuel shut-off that activates at 5600 rpm.

The best of the car is under the turbo lump. Early Buick turbos were less than exciting performers in real world driving. Dragstrip numbers were always acceptable, but in normal traffic cut-and-thrust the excitement provided was not a result of an excess of performance. The usual scenario (circa 1978) involved mashing on the throttle which was followed immediately by an automatic downshift, then, after a suitable pause, by the Quadrajet secondaries opening, the, after a bit, by useable turbo boost. Such an interval would have ensured by that point that often the driver had forgotten the reason for accelerating. So lifting the foot from the gas pedal caused the trans to upshift, the secondaries to close, and the turbo to return to sleep all at once lurching the driver forward testing poise, patience, and set belts. No fun.

That’s six long years ago and no need to look back. If the new setup doesn’t make boost at idle, it comes in soon after. The solenoid-controlled wastegate is programmed to allow a full 15 psi boost in 1st and 2nd dropping back to 8 psi at full throttle in 4th.

The injection is unique in domestic manufacture – an L-Jetronic style unit combining Bosch and Delco pieces with the control unite developed by Buick and Delco. It might be a good time to set the record straight about electronic injection – the basic patents were American (Bendix) and the early users – 1958 – were Chrysler and Rambler. The patents were eventually licenses to Bosch and first applied to the VW in the late ‘60s. S no need to feel dependent on, or subservient to, foreign technology ever again. The Buick-Delco-Bosch injection squirts fuel only when the intake opens – once every fourth stroke – instead of every second stroke as in most other systems. Immediate benefits are seen in emissions, or rather their diminution. Smoother low speed operation is also claimed, and, except for a slight low speed surge with a cold engine, seems to be there. The latest even-fire V-6 is easily the smoothest of that lot, probably a combination of less engine vibration and improved engine mounting.

The 3.8 turbo’s power peak is at 4000 rpm but power stays strong to 5000 and beyond. Like most turbomotors there is torque in abundance, and that of course is what makes it all move. It accelerates like no Buick since the GS series of old, and with 300 lb-ft (10 more than the new Corvette) it should.

The old basic A-Special bodies were designed in the early 70s, when aerodynamic improvement was far less important than formal rooflines and having a convenient demarcation line for the half-vinyl roof, with or without the carriage lamps. At the time of design, Cd we estimated, was about average at 0.465 (the original Datsun 240Z was 0.467). Half vinyl tops are still important, though certainly not in the market Buick is trying to reach with the GN, but the spring-loaded (for safety) hood ornament still remains. Despite that, using its new wind tunnel Buick has determined that the basic Regal, thanks to smoothing the front end, raising the tail, and flushing-mounting the quarter windows, is down to 0.444 Cd. The GN betters that by 0.03, due principally to grille changes and front and rear spoilers. An actual NASCAR Regal has a 0.375 Cd, again measured in the new tunnel.

Ride quality seems almost unimpaired by the tire, wheel, and suspension changes. An investigation, in the interests of journalistic endeavor, of course, of top speed produced 4000 rpm in 4th gear – just about 120 mph.

Handling is quite good, particularly when compared with the GN’s ordinary Regal and Regal Limited cousins. Understeer is present at a respectably high limit. Power makes the tail come around at moderate speeds, especially with a spot of uncharacteristically wet L.A. weather. In the dry, straight-line bite is all that can be asked of a stock car. Smooth-road roadholding isn’t in a class with the F-cars, but then why should it be? Center of gravity is higher, body-roll angle greater, with both contributing to camber change that does nothing to enhance high g-loadings. But considering all this, Buick has recorded .8+ lateral g. Our figures were nearly as good, and neither figure needs apology.

Fast transitions were a problem with our test car – the tires simply react more quickly than the chassis (our test car did not have the proper GN-spec bushings) can follow. The result is fairly rapid progress but with a lot of arm twirling and on an untidy line. Brake balance seems good, drive and squat are reasonable. occasionally after a hard brake application pulling occurred – the result of a sticking caliper? It righted itself, usually in quick order.

The spiffy seats contribute to the arm twirling in transitions. Despite the adjustable side bolster the Lears lake lateral locating ability. Buck and Bubba wouldn’t approve. The 3-position thigh supports have only one useable position and that’s a bit short for the long of thigh, the seat base cushion appears to have a crown in it, the back bolsters don’t locate or adjust. Maybe, in time, continual bun application will flatten the cushion.

The GN’s natural competition is the T-Bird Turbo Coupe. The T-Bird has a lighter feel, a less willing power plant (2.3 liters vs. 3.8, as well as the Buick’s higher boost and more sophisticated EFI make the difference), quicker handling augmented by tires that were figured into the chassis from the beginning. It’s a more modern car. The two cars from the very first opening of the garage doors have characters that differ more than their performance figures would indicate.

This year’s Daytona 24-hour was won by Bob Wolleck, a Porsche perennial, with an assist from Anthony Joseph Foyt, Junior. Wolleck would probably feel right at home in the T-Bird though the plastic trim and engine roughness might put him off just a bit. Foyt – well, Foyt probably invented the Nomex engineer boot. There’s no doubt he’d really rather drive a Buick.

The late Len Frank was the legendary co-host of “The Car Show”—the first and longest-running automotive broadcast program on the airwaves. Len was also a highly regarded journalist, having served in editorial roles with Motor Trend, Sports Car Graphic, Popular Mechanics, and a number of other publications. LA Car is proud to once again host “Look Down the Road – The Writings of Len Frank” within its pages. Special thanks to another long-time automotive journalist, Matt Stone, who has been serving as the curator of Len Frank’s archives after his passing in 1996 at the age of 60. During the next few months, we will be re-posting the entire collection of “Look Down the Road”, and you’ll be able to view them all in one location under the simple search term “Len Frank”. – Roy Nakano