The Cro-Sal Special

Published on Sun, Feb 28, 1993

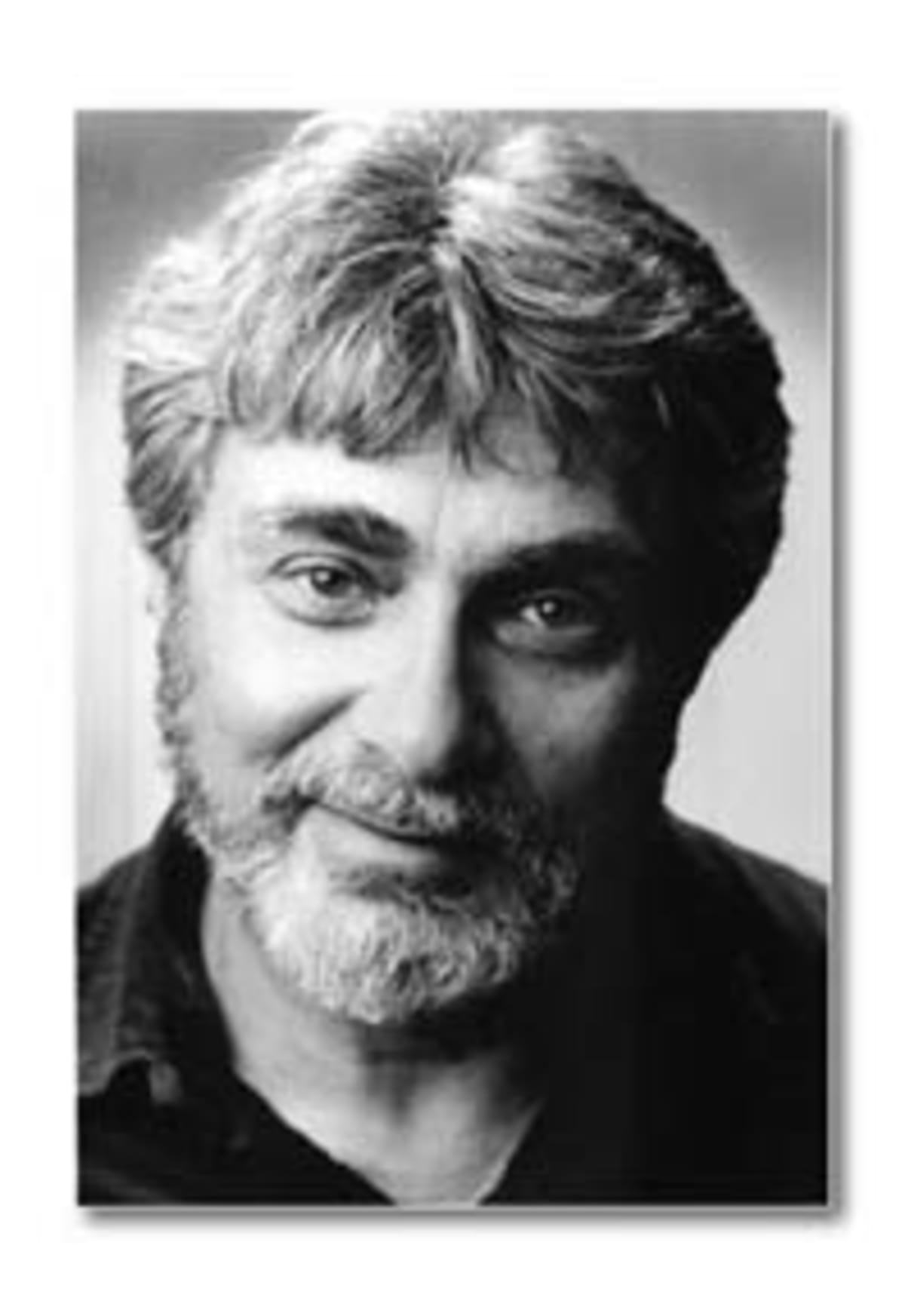

By: Len Frank

Cheetahs Always/Sometimes/Seldom Win (check one).

Len Frank on the Bill Thomas Cheetah sports car company and the winningest Cheetah of them all, the Cro-Sal Special. Written before his passing in 1996.

Originally printed in Road & Track magazine.

Original story photos by Ron Perry; as photographed here by Matt Stone

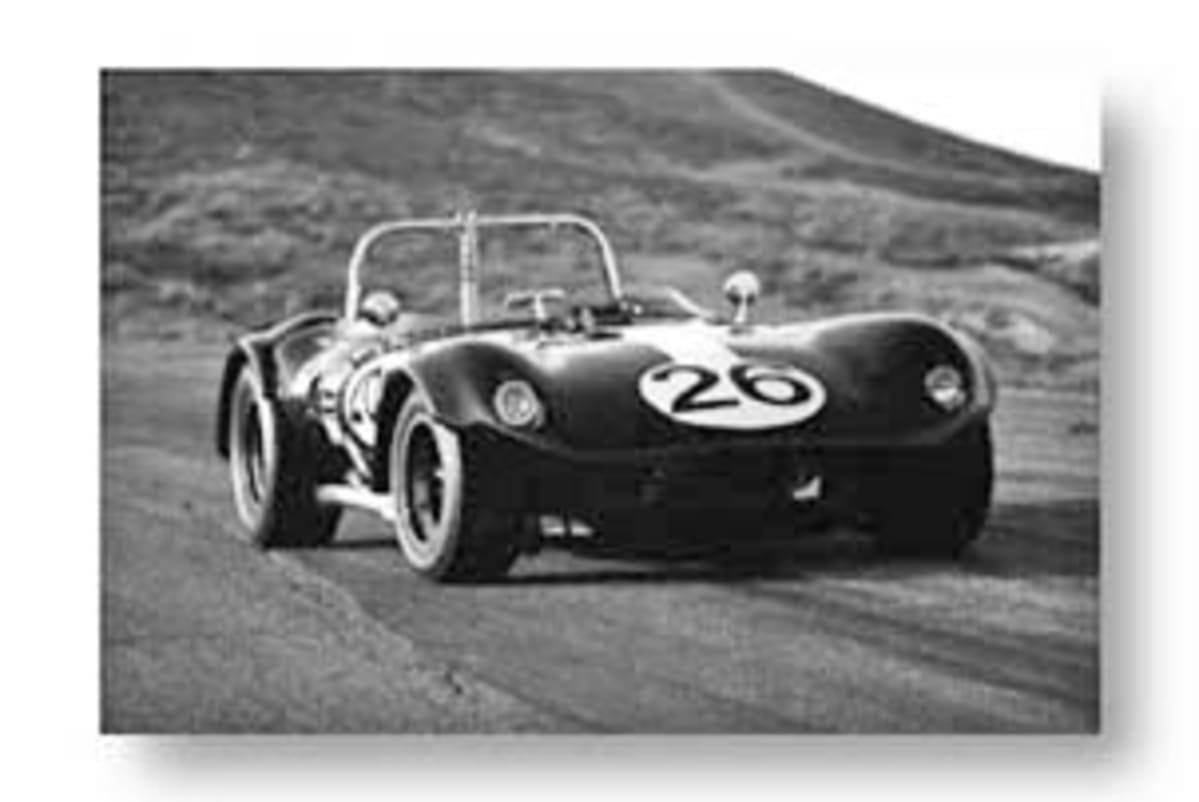

Let me get the hardware out of the way first, then go on to the more interesting stuff: there may have been a couple of dozen Cheetahs built, maybe not. Use that number for conversation. The first two built had aluminum bodies. The first car was “splashed” to make molds for the next batch. The car, both body and chassis, was designed by Don Edmunds. The plan was to incorporate as many stock Chevy components as possible, to make a lot of them, to homologate them as production cars.

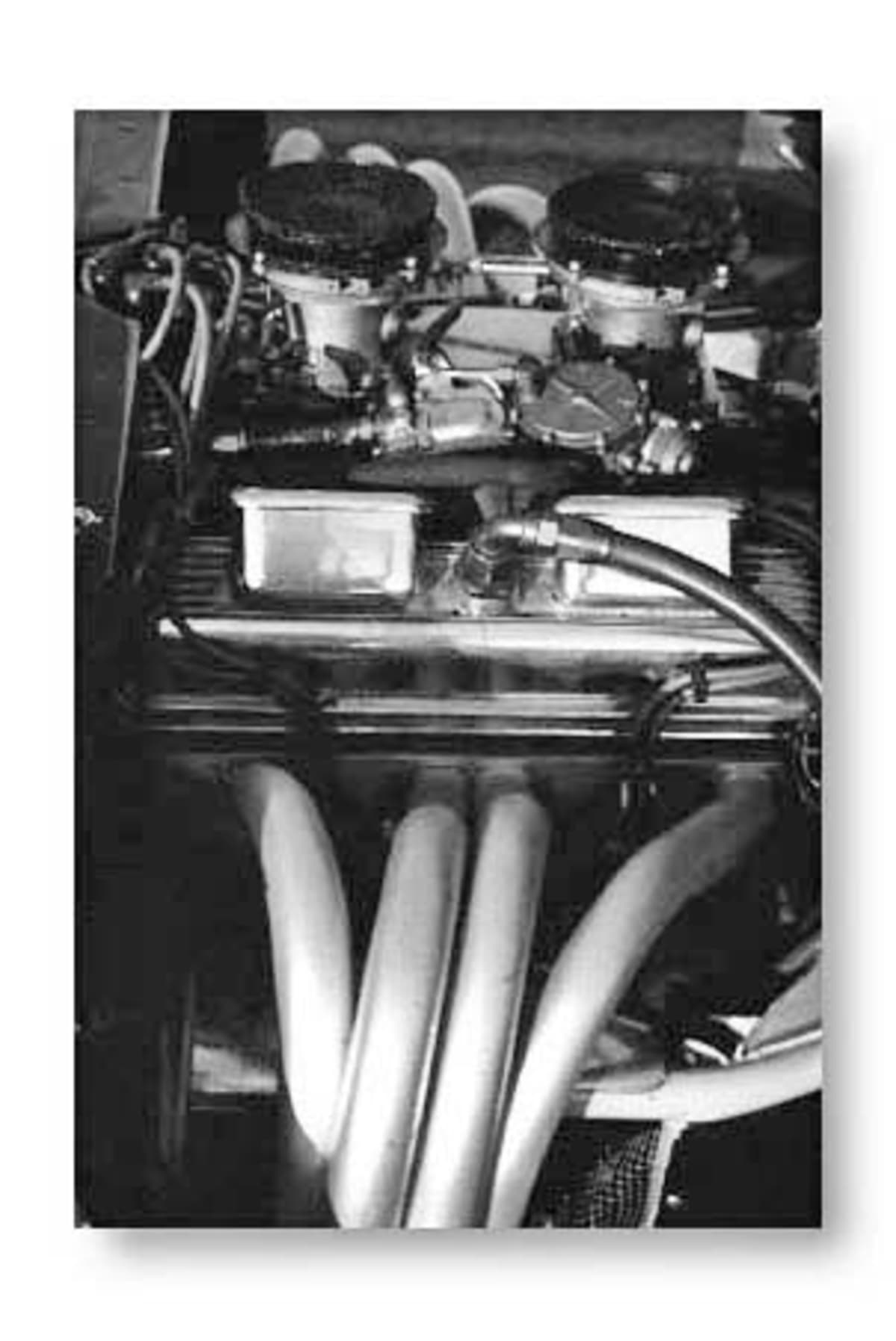

Thomas Cheetahs use Sting Ray differentials and half-shafts, Muncie (or Saginaw, or Borg-Warner) four speeds, station wagon front uprights and spindles, Corvette ZO6 competition drum brakes, and of course, great whacking Chevy V-8s, based on the 327.

Bill Thomas, although he has been a race team manager, a businessman, an expert witness, a promoter, a fabricator, is best known, at least among enthusiasts, as an engine builder. And the engine that he originally built for the first car had his own dual air meter modification to the Rochester fuel injection, a 3/4 inch stroker crank, and all of the other changes usually made to enhance the efficiency of a pump. The result was 520 real horsepower out of 377 cu.in.

The bracket that Edmunds designed to hold all of these pieces together was a chromoly semi-space frame—actually a nicely trussed structure of medium sized tubing with transverse hoops at strategic locations. Front suspension was by upper/lower tubular A-arms; rear, fully independent, geometry similar to the production Sting Ray but with tubing tuning fork-shaped trailing arms, and sprung all around with special Monroe coil/shock units. Heim joints are used in place of trunnions and ball joints. Rack and pinion also appears to be special. Weight is usually listed as 1510 lbs., and that is questionable. So much for the hardware.

The resultant car was too short, too wide, too cramped, too hot, too fast. The chassis was too limber, the glass bodies too thin, the aerodynamics more than a little questionable.

If you’ve read a Cheetah story before, you’ve read this all before. You’ve read about doors blowing off and 215 mph at Daytona and 185 at Road America. Some of that is even true. What you haven’t read, in some part, follows.

To write this short article I have talked with Bill Thomas III, son of the man whose name precedes “Cheetah”, Don Edmunds, who probably designed it, Dave Ryall, who has been collecting Cheetah lore for twenty years (because he says he likes the way they look) Ralph Salyer, the original owner of this particular Cheetah, Dick Barbour, third owner of the car, Max Crawford, Glenn Blakely, and Dennis Lyman, three craftsmen who helped make an awful mechanical sow’s ear into the best possible sort of sow’s ear.

I spent time with Stewart Van Dyne who asked me please to mention that his engine building shop does things like Gurney-Weslake V-12s and turbo Offys—not just Chevys. But, like Bill Thomas, he does build a hell of a Chevy.

Bill Thomas wouldn’t talk to me at all; Chuck Brahms, one of the car’s present owners, and I have been talking about very little else for more than two years.

The Thomas Cheetah is one of those would-have-beens, should-have-beens, like the Devin SS, like the Bocar, even like the mighty Shelbys.

We conveniently forget now, but the most honored, the most famous of them, the Cobra and the GT-350, though aesthetic and emotional successes were commercial flops—terrible commercial flops.

Like the others, the Cheetah is doubly aggravating to its longterm faithful because it has now become an automotive icon providing those who had faith in it originally a kind of bittersweet victory—emphasis on “bitter”.

“I-told-you-so” is better than nothing—but not much better.

Brahms had owned the #1 Scaglietti-Corvette, the one-and-only that had been built with fuel injection, racing suspension, etc. I had a small hand in its restoration and somehow had become the Designated Driver for its appearance at the Monterey Historics. That car suffered from too shallow a learning curve or too short a graph. The car was sold shortly after that one abortive race with Chuck muttering “never agains” and “I don’t need its.”

We found the Cheetah in a classified ad that advertised it as the “only Cheetah roadster.” In fact there were no Cheetah roadsters. What I don’t quite remember was why we were interested, but I was on my way to Denver to see it.

What I saw was a pile of Cheetah parts, piles of boxes, a pretty good frame, body panels, the Thomas dual air meter injection that all, with luck, would add up to the Cro-Sal Special, the winningest Cheetah of them all.

What I heard was the siren song of the salesman, a sort of keening that brings the suckers in from afar. Chuck bought the car for big bucks—probably, in retrospect, a good deal.

He also bought the car with the agreement that it be delivered to his shop (in the shadow of the R&T offices) fully restored, race ready. Certainly, in retrospect, a bad deal, a very bad deal.

It looked marvelous when it arrived, low, sinister, evil even, all dark blue paint and chrome roll bar, big Torque Thrust American Mags. Chuck had asked that a halon fire system be installed and the halon bottle, all thirty pounds, was installed on the passenger’s floor, held in with a single hose clamp.

The ignition key was missing—a call to Denver reassured us. It had never had a key, the switch was worn out and all it took to turn it on was a screwdriver…

Once we found the battery (under the right side headers hidden in the footwell box) and jumped it, it took starting fluid to get it running. In an industrial neighborhood crammed with automotive and marine shops, the running Cheetah brought them all out into the street.

Over to Dennis Lyman’s nearby shop to get the obvious stuff rectified. I found out that the thieves in Denver had bought the car from San Diego racer and car trader Dick Barbour. Dick had bought the car at auction in Auburn, Indiana in the mid-`eighties and started his own restoration. It was turned over to Max Crawford and Glenn Blakely (Crawford now runs his own fabrication shop in North Carolina, Blakely, when I talked with him was in Bill Elliott’s shop, now with Dan Gurney’s AAR).

I asked Blakely what needed to be done, he said “everything.” I asked him about the chromoly frame, he said, “the only chromoly in that frame are the pieces that I welded in. In fact he had mounted the engine solidly to front and rear aluminum bulkheads making the engine a stressed member and eliminating a couple of pounds of ugly rubber. He had also stiffened the frame around the differential mounts.

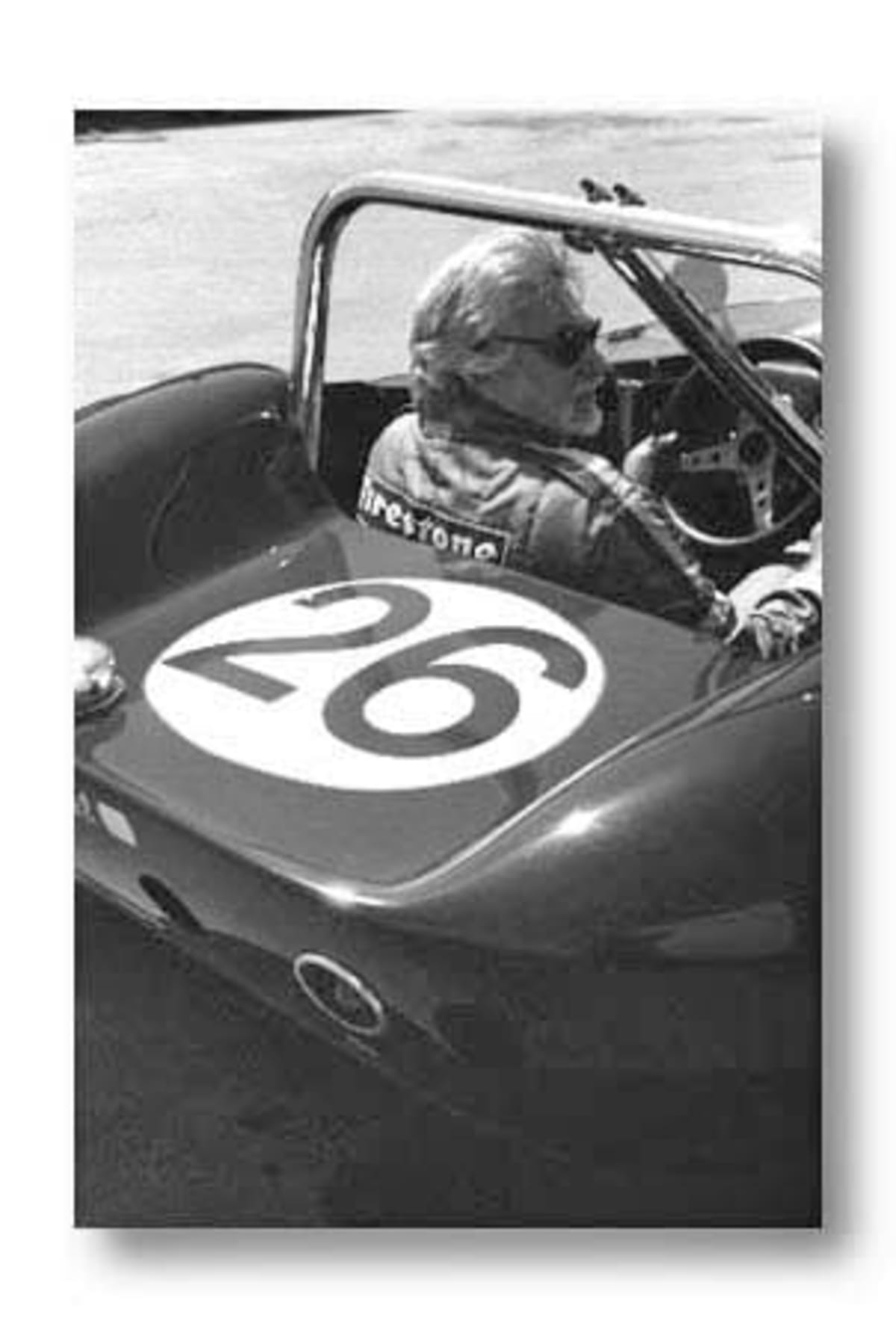

The first day we took the car to Willow Springs Raceway the temperature was over a hundred degrees outside the car, about two hundred inside. I had terminal jet lag but Chuck and Dennis seemed cheery enough.

My first time on the track (with Chuck exhorting me to drive carefully) the buffeting in the roadster was so bad that I couldn’t hold my head up. Change to an open face helmet, back onto the track. I’m wearing the usual three-layer Nomex suit-of-lights, Nomex shoes and gloves. No danger from fire, per se, but I may steam to death inside the suit. The chrome shift knob is burning my palm through the glove. It was just this effect that caused Salyer to cut the top off.

The whole effect is one of sitting in front of the world’s largest hair dryer while creeping around corners, weaving up the straights. The car won’t go straight—it pulls one way on-throttle, the other off-throttle. Brakes are barely adequate to pull the car up in the pits and strangely, as weak as they are, they pull too. The engine has no transition—it just explodes when the throttle is pressed.

Mercifully, the engine popped a seal and we all go home. The engine goes to Van Dyne’s—he finds four thou clearance between valves and pistons, big grooves in the main bearings, a crank good for 5500 rpm, a cam that comes in at 5000.

OK. This has to be wrapped up. There was another test session similar to, but slightly better than, the first. We were not accepted for Steve Earle’s Monterey Historics—a big setback—but we decided to take the car to Road America for the Chicago Historics. The Cro-Sal (for mechanic Gene Crowe and original owner/driver Ralph Salyer) Special won the 1964 June Sprints there in Wisconsin, the only major race ever won by a Cheetah.

Salyer, the late Jerry Titus, Jerry Grant, Allan Grant all went like hell in Cheetahs but running undeveloped against Lolas and McLarens (remember, the Cheetah was designed to be a GT car, to run against GTOs and, especially, Cobras) left very little showing in the result columns.

Fear and trepidation. Practice at Road America and we discover that the engine stops running when the throttle is released and the clutch depressed—it was doing it at Willow too but with all of the other problems that was overlooked. The brakes are still weak, still pull hard left. Finally, the tail shaft seal goes and the floor is awash in trans oil.

Chuck’s Solution involves sanitary napkins and duct tape but we make the race. Start twenty-fifth out of about fifty cars. I’m gridded behind a 427 Sting Ray Coupe—the start-finish

straight runs uphill and I can’t see the green flag until well after the Corvette. I have to wait for him to go before I can go. When he accelerates hard, so do I. I drive around him like, well, like a Cheetah passing damned near anything in a straight line.

With no brakes (one spin when a brake lining segment came off under “heavy” braking) and escalating oil temperature, I finish thirteenth.

We now have a proper 327-based 383 cu.in. Van Dyne-built engine with 472 hp, a new gearbox (the old one seized at Palm Springs), a new diff. It still stops running when the throttle is lifted at speed, it still pulls left under braking. We have been accepted for Monterey. I can hardly wait.

Top image: The inspiration for the Bill Thomas Special (photograph courtesy of pictures-of-cats.org in the public domain)

The late Len Frank was the legendary co-host of “The Car Show”—the first and longest-running automotive broadcast program on the airwaves. Len was also a highly regarded journalist, having served in editorial roles with Motor Trend, Sports Car Graphic, Popular Mechanics, and a number of other publications. LA Car is proud to once again host “Look Down the Road – The Writings of Len Frank” within its pages. Special thanks to another long-time automotive journalist, Matt Stone, who has been serving as the curator of Len Frank’s archives since his passing in 1996. Now, you’ll be able to view them all in one location under the simple search term “Len Frank”, or just click this link: Look Down The Road. – Roy Nakano